Posts Tagged Higher Education

March 13, 2020 or The Day Everything Changed

Posted by johnacaseyjr in Current Events, Updates on April 3, 2020

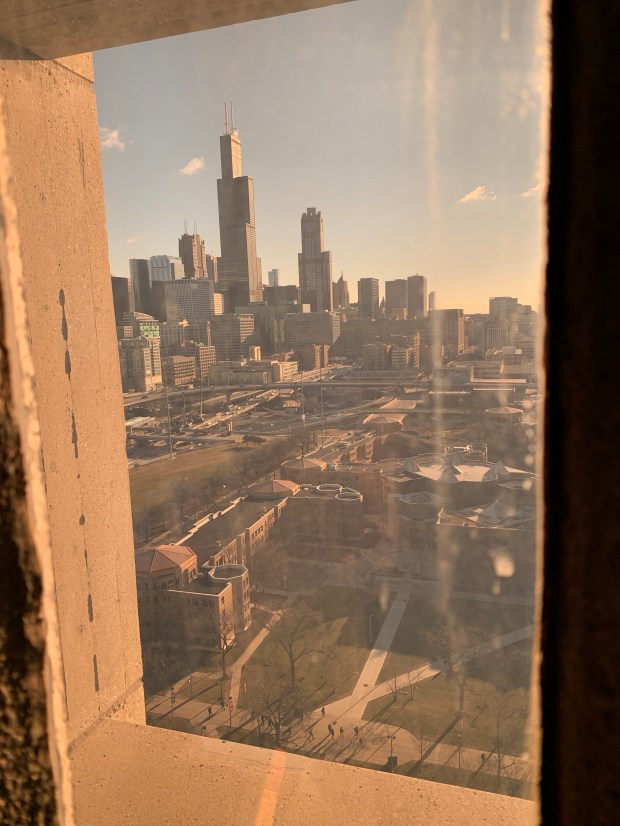

Note: the photo above was taken from my office not long before I left it on March 13, 2020.

Note: the photo above was taken from my office not long before I left it on March 13, 2020.

We knew that week that something big was on the horizon. Faculty had been told earlier in the week to prepare for the possibility of class cancellations and the need to teach from home. We knew that things were going to be different, but no one could appreciate just how much our lives would change.

The week before my wife and I had met her mother and step father for dinner out in Rosemont. She’d be leaving for a month in Spain the next day. I had misgivings. I told my wife “Are they really sure they want to travel. This coronavirus seems kind of deadly. A lot worse than people are saying.” I’d talked to my students from China. They were scared for their families. Not always getting accurate information on what was going on. Almost all of them had been wearing masks already back in January. I looked at my father in law, already frail from Parkinson’s disease, and wondered if I’d ever see him again.

But we pressed on. We pressed on because no one ever wants to believe that a calamity of this scale can happen. Especially to them. This is historic shit. It belongs in sepia tone. Not in my community. Not on my Facebook wall. But it happened anyway. It happened the week of March 13, 2020.

That week began with premonitions. I told my students to expect guidance soon from the university on what to expect in the weeks to come. I told them to wash their hands and clean their phones and computers regularly to help them stay well.

On Wednesday, I got home. My wife had a hair appointment so I drove the car. While eating dinner, I saw the President give a speech. The US borders closed to foreign travelers. I thought of my mother in law still in Spain. I texted my wife. “Can she get back in the county? What will happen? They better leave now.” Her mother decided to stay a few more days. It would soon blow over. No one seemed all that worried in Bilbao.

Then on Thursday sports leagues started to shut down. First the NBA and then the NHL. Suddenly it seemed real. Without sports to distract us, people began to freak out.

I decided on Wednesday to make Friday my first distance learning class for my First Year Writing Students. But I still had an exam to proctor for my American Literature class. I came to an eerily quiet campus, quieter than I had seen it since 9/11 and taught my comp classes on line from my office while waiting to proctor the exam.

Going into the classroom building, I discovered my classroom had been locked. An ominous sign. We took the room next-door because it was unlocked. Most classrooms already seemed empty. The custodians nervous. Wearing face masks and gloves as they swept and sanitized the building.

I gave my students the exam and they completed it in silence. Were they nervous about the exam or the possibility of catching what was now being called COVID-19? I have no idea. The last student finished around 3 pm. Those still remaining packed up to leave.

As I walked outside the classroom and prepared to head back to my office, a student stopped for a moment to talk to me. “What do you think will happen?” “I don’t know.” I said. “We’ll try to make things work on line, but I don’t see us coming back to campus this semester.” “I don’t know,” he said, “some classes don’t work well online. Like this one.” “Yeah,” I said, “but we don’t have much of a choice. We’ll all do our best. Just be patient with me and I’ll be patient with you.” I wished him the best and told him I’d pray for his grandparents with whom he lived. He worried about their health just like I worried about that of my family. My dad has COPD and my mom MS. Even a regular cold is a cause for concern. And this shit, ain’t no cold or flu.

Going back to my office, I started to pack things up in my bag. I wondered when or if I would ever see this space again. I’ve never liked the Brutalist architecture on campus, but I felt a sense of sadness at losing the routine of going to work and coming home again. I put away things I knew I would need and headed outside to wait for my wife to pick me up in the car.

Deserted. Quieter than 9/11. That was my impression as I waited. Today was the end of something. I didn’t know what. I just knew that what came out on the other side would never be like this again. When I got in the car, I told my wife “Let’s go out to eat. This will probably be our last normal meal for a long time.” We went to Portillos. To date, it is the last night we have been out to eat.

We then decided to go to the store. We thought that maybe Friday night would be quieter than Saturday afternoon. We were wrong. The Jewel was more crowded than I had ever seen it before. Store shelves decimated of the most random things. Someone had bought all the cheap frozen pizza, all the onions, all the flour. But they had left behind the TV dinners, the eggs, and the yeast. There was also a lot of alcohol to be had. But no toilet paper. Thank God I had bought some on Wednesday before the panic buying had hit high gear.

That night we brought our purchases inside in stages along with the items from work. My wife would still have to go to the office for a few more days. Then the governor would shut the state down, sending us all home for an indefinite period of time.

So here I sit. Writing this blog post today on April 3, 2020. Like many of you, I feel like I have lived more than a year in a few weeks. And yet, the bad news continues. Death upon death. Disaster upon disaster.

Who knows what the future holds. But my mother in law and her husband eventually got home before Spain and all of Europe shut down. They are both healthy. Thank God. As are my family so far.

I work from home now. Teach distantly. Grade papers as before. Looking over my shoulder as history happens. Reminded again of the tenuous hold humans have on their environment. We have always been mastered by our setting. It’s just that living in a city, one not prone to many natural disasters, has given me the privilege of ignoring this for a long time.

No more. Only God and our immune system can tell us what the future holds. May they both be kind to you and yours.

Director’s Corner (NEMLA Blog Post #6)

Posted by johnacaseyjr in Higher Ed, NEMLA, Updates on January 28, 2016

Greetings from Chicago! It’s cloudy and cold outside today as I sit and write this blog post but unlike the east coast there’s no snow on the ground here. Perhaps I’m crazy, but I kind of miss the snow cover. Haven’t had a chance to drag out my cross country skis at all this year.

My last blog post was written before Christmas. I hope you’ll forgive me for taking the month of December off as I was focused on visiting my family and trying to wrap up a bunch of projects that had collected on my desk over the fall semester. In that November post I examined the use of electronic texts. This post will cover the topic of Educational Technology.

I first became aware of the term “Educational Technology” through Twitter, specifically the tweets of Audrey Waters. Before reading some of her posts on Hack Education, I had never heard of the term but I was well aware of the programs and services the term described. Most familiar to me is Blackboard, the Course Management System (CMS) used at UIC. I was also familiar with the various products such as MyWritingLab that Pearson had long been promoting amongst writing faculty on campus. Apparently they have a version of this My(fill in the blanks here)Lab for every discipline taught on campus.

Most faculty entering the market for Educational Technology are either lost in a field of options made more confusing by technical jargon or are simply content to accept whatever technological tools are provided to them by their employer. Few of us have the time or inclination to ask what types of technology are cost effective and, more importantly, what tools will actually enhance what we do in the classroom.

I experimented with several different types of educational technology in my First Year Writing classroom during the Fall semester of 2012. The course I was teaching (ENGL 160) is designed to teach students short genres of writing such as the argumentative essay and proposal writing. At the time, the course was balanced between academic and non-academic genres. You can find a link to the syllabus under the Teaching Materials tab of my website. It’s called “First Year Writing:Genre and Argument.”

I chose the Profile genre as well as that of the Manifesto to help students practice writing in a public context. Since many of these non-academic genres are published online, I decided to have them work on the text of their assignments in Microsoft Word but then import that content into Google Sites for the Profile and Tumblr for the Manifesto. Neither of these tools are typically considered educational technology, but that is part of my point. Marketers have software and services that they claim are designed with your classroom in mind. But any technology can become educational technology if you provide the proper pedagogical context for it.

In the case of the Profile, Google Sites was chosen as a simple web design tool that would allow students to craft an online Profile for the person they interviewed. This person was someone on campus at UIC that they felt others should know. My favorite example was the student project that focused on a custodian in her dorm complex. The hope with this writing assignment was that students would not only learn basic rhetorical techniques associated with the Profile genre since its creation but also would learn how to translate those analog skills into a digital environment. It worked generally OK. My one frustration was with my choice of platform. Google Sites proved easy to me, but not my students who struggled to figure out its design interface. Tumblr was a different story. Most of my students had already used Tumblr before and some had profiles on the site. They also like the photographic emphasis of the platform as opposed to the text heavy set up of Google Sites. They used Tumblr effectively to create a Fashion Manifesto (based on the popular Sartorialist blog) that was designed to teach UIC students how to be fashion savvy on campus.

This academic year our program has begun shifting to primarily academic forms of short writing. I haven’t taught this particular course in a while so I’m not sure how that would shift my choice of educational technology. One thing is for sure, however, I like choosing and shaping the tool I want to use rather than simply taking something given to me by an educational technology designer. This saves students money but is also gives me flexibility as an instructor to shift from platform to platform as I see fit rather than being locked into a deal with a major publisher or software developer whose staff don’t fully understand the needs of my class. The downside to this approach, as I’m sure you’ve already guessed, is that it does take a bit of time to create your own context. Perhaps that’s why I’ve stepped back from the process of platform selection in the last few semesters to more traditional pedagogical tools. I’ve even tried, Lord help me!, to make Blackboard work to my advantage. No luck on that yet. It still serves mainly for me as a clunky version of Dropbox.

Faculty on campuses around the world are doing some excellent work with their students creating their own educational technology. Two that come to mind are Chuck Rybak at the University of Wisconsin Green Bay and Jeff McClurken at the University of Mary Washington. There are many more. What these faculty have in common is a desire to learn the logic behind technological tools and create a context for them in the work they do in the classroom. Again, this takes time. It also takes money and at the very least a minimal amount of institutional support. Unfortunately, at my institution security concerns and legal liability issues trump the desire for experimentation. As I often joke with colleagues, the answer to any question asked of our university computing center is “Blackboard.”

For anyone reading this post who’s interested in delving into the world of educational technology I recommend first finding a partner to work with. This could be either another faculty member in your department who shares some of your interests, a colleague in a department such as computer science who would be interested in collaborating with a humanities scholar, or a librarian willing to help you create your own educational tool. Not only will this save you time, but it will address the issue of funding, which is always a concern with new projects. Free online tools are abundant but not always easy to find. Adapting these tools might also cost you some money for things like hosting fees and access to advanced editing tools.

What I don’t recommend is simply taking the tools offered by educational companies and using them in your classroom. Blackboard is useful. Especially the announcements, file sharing, and grade book. But using it teaches me nothing. Nor does it teach my students. All it does is deliver content. The point of educational technology should be more than content delivery. It should be the act of learning how to deliver content through an electronic medium (a.k.a. digital literacy).

I hope you all find the tool that works best for you and don’t get distracted by technology that you don’t need. If you are a faculty member and have some tools that you particularly like or educational technology projects you’re proud of and would like to share with my readers, feel free to comment on this post.

My next post is going to shift from pedagogy to research. I’ll be sharing with you some of the themes associated with my next book project. A work very much “in progress.”

Until next time…

John Casey

Director’s Corner (NEMLA Blog Post #5)

Posted by johnacaseyjr in NEMLA, Updates on December 1, 2015

I hope that you all had a Happy Thanksgiving and are on track for a successful end to your fall semester. After getting back from a visit with my in-laws in Springfield, Illinois, I find myself swimming furiously in a sea of student papers, articles and manuscripts in need of peer review, and revision of my own writing. There’s also the constant rush of students in and out of my office now that they’ve discovered (belatedly) the location of my office as well as my posted office hours. Ah, the glamorous life of the academic. ; )

In my last blog post, I focused on the use of Twitter for academic purposes. This month I’d like to discuss the use of electronic texts in the classroom. Among my colleagues at UIC, there is a robust debate over whether it is appropriate at all to invite the use of electronic devices in the undergraduate classroom. Some faculty choose to prohibit phones, tablets, and laptops from their classrooms and require students to purchase hard copies of books and print out articles for discussion in class. Other faculty on campus only use electronic texts, print sources than have been scanned or coded into an electronic format or sources that only exist electronically.

My approach is a hybrid of these two poles. Certain books I prefer to have students buy in hard copy or print out. These are typically sources that we will be reading closely or analyzing multiple times. Other resources, mostly contextual in nature, I prefer students to access electronically as needed. The rationale behind this decision does have some research to back it up, but is based largely on my teaching experience as well as feedback I have received from students. “Close reading,” “Analytical Reading,” “Hermeneutics,” call it what you will, depends upon a form of deep concentration that it is hard for us to achieve when we are scrolling up and down a computer screen. True (as Franco Moretti points out) readers have been engaged in superficial readings of texts for as long as humans have been writing language down. However, it is just too easy for me to shift to Facebook, Twitter, or another document when reading an electronic text or skim rapidly across the words on the screen without registering much beyond the “gist” of what I have read. With a book or article in hand, I feel pressure to go back over text my eyes have lazily gazed over and highlight/annotate the parts of the text that seem significant.

Students in my courses have generally agreed with this assessment. Contra Cathy Davidson whose most recent book, Now You See It, champions the benefits of distraction, students on the UIC campus have complained to me about how hard it is to focus with their phones buzzing and pinging with updates and notifications from various apps. They have also found the technological limits of wifi, software compatibility, and device battery life a challenge. We joked in my Introduction to Literary Criticism and Theory course several semester’s ago that the main vulnerabilities of the codex as interface are water and fire. Other than that, as long as you don’t lose the book or print article, you’re good to go.

These significant drawbacks to the electronic text have often left me skeptical about the best way to use them (if at all). As I mentioned earlier, the main ways in which I have found electronic texts useful have been contextual in nature. This includes bringing historical documents such as newspaper articles, letters, photographs, and maps into the classroom. These supplementary texts help us better understand the social background of the writings we are analyzing. Another effective use of electronic texts has been when a work is otherwise unavailable in print for students to read. Most of the authors I teach and research are now part of the public domain, making their work freely accessible for all to distribute in whatever way they see fit. What better way to appreciate the literary context that influenced an author’s aesthetic than to read the works of his or her contemporaries for comparison.

Perhaps the greatest source of influence in my decision on whether or not to assign an electronic text, however, has not been pedagogical at all. Instead it has been driven by the rising cost of student textbooks. The anthology I used in my Introduction to Literary Criticism and Theory cost students on average $115 to buy. Renting the book lowered the cost to around $70. This might not seem like much in comparison to texts in other courses that can cost significantly more or software programs that students are required to buy for majors in the architecture and the sciences. Yet the cost adds up over time. Whenever I assign a print book or article, I make sure that we are in fact going to read the text exhaustively. That it is in ever sense a “required” text for the course. Anything that might even be vaguely considered supplemental, reference oriented, or “recommended” is assigned in an electronic format to save costs.

Now at this point it is worth acknowledging the hidden and often not so hidden cost of e-texts. Publishers come by my office on a near constant basis around this time of the year, particularly Pearson. They are more than eager to sell my students access to proprietary websites that mediate between them and the things they will be reading. One example is MyReadingLab. The allure of such technology is that it lessens my workload in and out of the classroom. But is it worth the cost? To me, at least, it isn’t. I would rather find online resources that are either free or more affordable and link students to them via our course management site, Blackboard. There is also the transfer of costs to students in printing fees, my xerox budget has been cut dramatically by my department, as well as the cost of buying a device to read electronic texts on. Sure, a sizable number of our students have smartphones today, but who wants to read a novel on a iPhone? Even youthful eyes are strained reading that tiny print.

The only honest way to conclude a discussion of electronic texts in the classroom is to admit that the data is mixed. Their are numerous disadvantages to moving away from print texts but there are also many benefits. I hope to have a fruitful discussion on both during my round table presentation in Hartford on “required texts” and “authoritative” editions of literary works. In the meantime, if you have been using electronic texts successfully or unsuccessfully in the literature classroom, let me know. If you haven’t tried using them at all, experiment with a few this spring. Teaching and scholarship after all are a great adventure. Why else would we keep slogging along through the seemingly endless writings by students and colleagues that call for our attention on an almost daily basis?

In my next blog post, I intend to revisit my comments on Pearson and other educational resource providers (including Blackboard). What should scholars know when they enter the market for educational technology? How can we choose the tools that make sense for our pedagogy when we are limited by lack of knowledge, money, and sometimes institutional bureaucracy?

Until next time….

John Casey

A College By Any Other Name

Posted by johnacaseyjr in Higher Ed, Updates on November 4, 2012

Mid-terms have come and gone at the University where I teach and work as an administrator. With their passing, students are left to ponder just what it will take to get them through the rest of the semester. Some will take advantage of the services available to assist them as they try not to buckle under the growing burdens of their blended school work, jobs, and social life. An even larger number, however, will fall by the wayside and drop out of their classes.

This is especially true of the First Year students I teach. ACT statistics from 2012 show a first to second year retention rate at all of the United States’s colleges and universities they surveyed of approximately 67%. Even if the financial burden of going to college were not as bad as it is today, this rate is still alarming. It is indicative of an educational system that is good at persuading students to enroll, but not as good at ushering them towards the completion of their degree.

Part of the problem is the message that parents, educators, and public figures such as President Obama send to prospective students. First they tell them that college is a surefire ticket to a better life. And then they convince prospective students that any college and degree program will do. All the would be students need concern themselves with is that they hurry up and get a BA before its too late.

A major problem with this message is that the first assertion is a selective interpretation of the truth. Statistics show that “on average” college graduates have greater earning power than those with only a high school degree. The reality, however, is much cloudier. Earning power depends largely on the degree earned and the school granting the degree. As more Americans have Bachelor’s degrees, employers can be more selective. This makes the subject studied and the network of potential recommenders that a well-known school can provide more important than ever. Also, it is worth noting that the only reason college earnings have remained higher than the take home pay of non-college graduates is that the average wage of high school educated employees has plummeted since the 1980s.

Armed with this faulty information, students are then fed the equally faulty perspective that all institutions of higher education are essentially alike. How many students do you know of who are savvy enough to parse the distinction between a college and a university? How many faculty can do this for that matter? What does a community college really offer? How about for profits? Students are left with the impression that college is vital to their future, but then are left essentially adrift to figure out where they should go on their own. Is it any wonder that undergraduates are often better at comparison shopping for a smartphone than they are at picking out a college?

One way to alleviate this problem is to be honest with would be students. Don’t discourage them from going to college, but explain that, depending on what career path they are intent on pursuing, a college degree might not be necessary. There are numerous certificate programs and high school vocational programs that can place students in satisfying careers that pay a living wage. Additionally, there are two-year colleges that can either serve as a place for would be students to discover what they are interested in studying or provide them a skill that is immediately applicable to the workforce.

Making these career track options more visible and more viable will then enable colleges and universities in the United States to stop marketing themselves as job training centers. Four year institutions of higher learning should busy themselves imagining the jobs of tomorrow rather than placing its students in the popular fields of today.

Revisiting the Digital Divide

Posted by johnacaseyjr in Higher Ed, Updates on October 15, 2012

Much of the research on the “digital divide” focuses on individual users and demographic groups that have traditionally had limited access to technology. A recent study by the Pew Research Center continues this trend. Their findings indicate that thanks to mobile technology, specifically the smart phone, internet use among all social groups is increasing. Fear of technology is also fading as once excluded groups learn digital literacy.

Although these studies are heartening to read, indicating gradual progress towards greater access to technology for all citizens, they fail to take into account the digital divide that exists within educational institutions. While television, radio, and internet news providers have been busy bashing the teacher’s unions and tearing apart the educational policies of “No Child Left Behind,” precious little has been said about the uneven technological infrastructure of our nation’s schools.

For every school with access to i Pads and state of the art computer labs, there are hundreds with only a handful of aging computers (usually in the library) that are available on a first come first served basis for internet research and word processing. This problem is endemic throughout the current educational system, reaching as far as the ranks of higher education.

Right now I am writing this blog post at home on my personal laptop. Partially this decision was made voluntarily, as I wanted to write during the evening in the comfort of my home and not use work resources for non-work related activities. Even if I had wanted to write this post earlier at work, however, I could not.

I share an office at my institution with four other Non-Tenure Track Faculty (NTT as we’re calling them these days). At one point, we had a desktop computer that was five years old. Not surprisingly given the CPU intensive nature of WEB 2.0, this machine died during the summer semester.

In its place, next to the CRT monitor (i.e. the kind that looks like an old TV), mouse, and keyboard of the old computer, sits a seven-year old laptop–a PowerBook G4. This machine was wrangled from the department after over a month of hectoring our IT guy. I had never even heard of this particular brand of Apple laptop so I took the time to search for information about the system on Wikipedia. It turns out that the “new” computer in my office is the precursor to the now ubiquitous Mac Book.

With its limited CPU power and an outdated browser, the most I can do with this laptop is check my email and read websites that aren’t overly graphics heavy or interactive. On most days I go upstairs to the computer lab and wait to use one of the three computers in our departmental computer lab. I also have the option (unlike most of my colleagues) of using the computer in my other office where I serve as an undergraduate studies program assistant.

Added to these frustrations is the lack of wireless internet access in either of my offices, which prohibits me from bringing my personal i Pad to work and getting around the technological limitations of my work space. At one point, I was able to “hack” my way into the network by plugging the internet cable in my teaching office into my own laptop, but as of today our internet connection there is down. This also makes it impossible to use the telephone in that room as my institution switched a few years ago from regular phone service to VOIP (voice over internet protocol).

If we move from my early twentieth century office into the classrooms where I teach, the situation is only slightly better. In a course I designed to teach digital literacy and multi-modal writing to my students, the most advanced technology in any of my three classrooms is a flat screen monitor with a VGA cable that allows me to plug in my own laptop and display its screen on a 25″ television. Wireless access is available in all three rooms, but that assumes that my students can afford to bring their own technology to class as I have.

“Plug and Play” is better than nothing in a world where technological access is no longer a luxury but a precondition for education to take place. Yet it places the burden of technology’s cost on the students and educators. Not only is this unfair, it also sends a strange message to our students: “You need to be educated for the jobs of the 21st century, but we will not provide the tools.” No wonder self-learning is coming back into fashion. Why pay for school when you can buy a laptop and let the internet teach you the skills needed to survive in a tech-driven world?

Now I should perhaps qualify my statement/rant above by reiterating the fact that I am a NTT faculty member. I’m also an English Professor. Perhaps things are different for the TT faculty in my department or are significantly better in other programs at my institution. My suspicion, however, is that while the technological infrastructure might be less antiquated than what I described above it is still inadequate to meet student needs.

When we talk about the digital divide, we need to remember that surfing the internet is a skill easily learned alone at home. Using the web to your advantage, however, is a skill that should be learned collectively in the classroom. Regrettably, this can’t happen when many educators work in an environment designed to teach Baby Boomers to fight the Red Menace.

Quality Over Quantity–Computer Assisted Grading Revisited

Posted by johnacaseyjr in Higher Ed on April 3, 2012

A Reuter’s report describes recent efforts to create computer software that could scan and grade common errors in student essays. Mark Shermis, Dean of the College of Education at the University of Akron, is supervising a contest created by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation that would award $100,000 to the programmer who creates an effective automated grading software.

Shermis argues that if teachers weren’t swamped by so many student papers in need of grading, they would assign more writing and student’s would greatly improve their written communication skills. He sees this new technology as an aide to the overworked writing teacher rather than a potential replacement.

Steve Graham, a Professor at Vanderbilt who has conducted research on essay grading techniques, argues, in contrast, that the replacement of writing teachers by grading software is not only “inevitable” but also desirable as “the reality is humans aren’t very good at doing this.”

As the writer of the Reuter’s article notes, talk about paper grading software is not new. It began in the 1960s. Now, however, technology has reached a level where such grading is not only possible but also probable. But the question still remains: Is it a good idea?

Leaving aside for a moment the question of faculty employment, machine grading sidesteps a more important question than how to get students to write more and grade that writing effectively. Namely–what is writing and who is responsible for teaching it.

In too many schools writing is viewed as the “problem” of the English department. Students are sent to writing classes to learn essay structure, research techniques, and grammar. Only the last of these is universal. The other two skill sets are discipline specific. I guess that explains why to my students everything they read is a novel and every paper a literary analysis. They’ve been taught after all that writing equals English.

If we really want students to learn not just writing but effective communication, parents, teachers, and administrators need to spread the responsibility for this instruction across the curriculum. Some schools already do this but most are content to leave communication training to literary scholars. Machines won’t change this. They will be programmed to evaluate whatever curriculum is currently in place. Until the curriculum is changed, the machine will not only replicate the error but multiply it.

Moving on to the issue of employment, part of my unease with a machine that grades papers is it would most likely put me out of a job. I have 48 student essays in need of grading that are staring at me right now as I pen this post. Of course, the curricular changes I suggest would more than likely have the same effect, with or without machine assistance. The way to counter this, however, is to lower class sizes.

This is the other aspect of the issue that is completely ignored by most research. If class sizes are lessened, not only will more teachers have employment but writing will become a less onerous task to teach and evaluate. It could also then be meaningfully integrated into the entire curriculum and not remain the purview of the English Department.

Would such changes cost a lot of money? Yes. But it is a good investment. Far better than the money we’ve wasted in Iraq and Afghanistan and the even larger sums of money we spend incarcerating drug offenders. It’s even better, dare I say, than the cost of a certain software currently being designed to solve all my problems.

Knowledge Is Power

Posted by johnacaseyjr in Higher Ed on February 11, 2012

Somewhere in the top drawer of my dresser is a metal insignia that reads Savoir C’est Pouvoir–Knowledge Is Power. That insignia was given to me by my uncle years ago when he left the 82nd airborne to return to civilian life. He had served for several years as an intelligence officer with his unit and that service was reflected on the insignia he wore on his maroon beret.

What is true for the armed forces is often equally true in other areas of life. In this case the quest to reform the conditions of teaching and learning in higher education. To achieve any kind of victory, it is first necessary to understand what exactly you are up against. Good data can save lives on the battlefield and it can shape for the better (or worse) the future of students and teachers in the college classroom.

The task to gather accurate intelligence on Adjunct labor conditions began with a vengeance last week as Josh Boldt, an Adjunct Professor of English at the University of Georgia and fellow attendee of the New Faculty Majority summit, created a Google docs spreadsheet where Adjunct faculty can list their salaries, benefits, and working conditions. Here for the first time the general public can see in one place how much Adjunct faculty make at institutions throughout the United States and (in some cases) the world. I’ve added my information to the spreadsheet. I’d encourage you to do so as well.

Reading through all the information on the spreadsheet is a bit daunting and at some point it will need analysis and visualization to work as an organizing tool, but I anticipate some great coalition building campaigns emerging from out of this data. Administrator’s can easily dismiss claims based on ethos and pathos but they can’t dismiss the logic of numbers. A quick scan of the data on this sheet shows that the median salary for Adjunct faculty is well below the suggested MLA guidelines and is far lower than the amount needed to sustain oneself let alone a family.

In a recent post to her Inside Higher Education Blog, College Ready Writing, Lee Bessette extols the benefits of this “crowdsourced” project on behalf of Adjuncts everywhere and I am inclined to agree with her. My only quibble is with her use of the word “hero.”

At the New Faculty Majority summit I was frequently the annoying pragmatist who pointed out the need for data and clear talking points not simply to push our adversaries back on their heels but also to energize the people we hope to form into a coalition to change higher education. Call it lamenting, kvetching, carping, whatever you like–the fact remains, I have been witness to and participant in ALOT of failed organizing campaigns. I’d like to think that I have learned something from those experiences and what I was saying came from that perspective.

We don’t need heroes in the quest to reform higher education. Instead we need patience, perseverance, and clarity of vision. These are the qualities that inspired Srdja Popovic in his campaign to topple Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic and later guided uprisings in places such as Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya.

Let’s not kid ourselves. The status quo works for the people in power. If it didn’t, contingent labor wouldn’t be expanding and it wouldn’t be invisible to the general public. To make it stop working will require thousands of micro-strikes against it rather than one dramatic lunge. We are small but mighty. Non-violent guerilla war against corporate higher education has begun.